I hope you’ve heard about the Starlink constellation of satellites that is being put into orbit this year by SpaceX. Starlink is a global network that will provide satellite internet services with better speed and lower latency than current satellite internet. The difference is that instead of being located in the geosynchronous satellite belt 36,000 km above the Equator, the first wave of Starlink satellites orbit 550 km above Earth’s surface in a web of inclined planes.

362 Starlink satellites have been put into orbit so far, and SpaceX plans to continue to launch more, in batches of 60, until a complete “shell” of almost 1600 satellites is up there. Secondary constellations of thousands of Starlink satellites at different altitudes may follow. Starlink is not the only satellite internet provider that is planning a constellation like this: a company called Oneweb plans to launch a 650-unit constellation. SpaceX’s advantage over other providers is that they also own the rockets they are using to loft Starlink, and they can re-use those rockets several times.

In this case, the rocket scientists and the astronomers do not always get along. Thousands of extra satellites in low Earth orbit represent interference for optical astronomy, especially during local summer when satellites are in daylight for longer periods of night at Earth’s surface. These spacecraft could cause a wave of UFO reports. Some of us remember the beginning of the Iridium satellites and their bright “flares”, and comparable concerns we had for their effect on astronomy. Iridium has now gone away, but Starlink may produce more interference. SpaceX has demonstrated techniques to make the satellites dimmer and to minimize interference with astronomers in future.

Various K-band radio communications used by Starlink could also cause interference for radio astronomy. Also, the sheer number of new satellites poses a problem for orbital debris collisions, and SpaceX is implementing some new kind of collision avoidance scheme to avoid the possibility of a “Kessler Syndrome“, in which a chain reaction of collisions between satellites could make low Earth orbit unusable.

Although most of the Starlink constellation hasn’t been put into orbit yet, we know that the 1,584 satellites that are going up will be split into 72 different planes of 22 spacecraft each. I did a little extrapolation from the spacecraft already in orbit and generated a satellites file that Starry Night can use that simulates what these spacecraft will look like in the planetarium sky once they are all in orbit.

These Starlinks have imaginary names using a system “STARLINK AAAA, AAAB, AAAC…” This file doesn’t represent real satellites, and the method I used to make it requires replacing the satellites file already used by Starry Night. It is not hard to locate the files to be replaced and rename them for a while as we test out this file consisting of only Starlink satellites, so the generally useful data can be preserved. But if you are used to using views of the International Space Station or the Hubble Space Telescope in your Starry Night shows, that can’t be done at the same time as testing out this Starlink simulation.

The attached two files, Satellites.txt and SatelliteMagnitudes.txt, are text-parsable and represent the orbital elements of the satellites, and some data about how bright they are. The orbital elements are in the standard format used by NORAD, the US Air Force, etc., for this kind of data, known as Two Line Elements.

For the time being, let’s assume we are testing this on SciDome Preview Suite. Go to the following folder location on your Preview Suite computer:

C:\ProgramData\Simulation Curriculum\Starry Night Prefs\Sky Data

If you can’t see the ProgramData folder, the only problem is the ability to see hidden folders. Please contact me for advice. The Sky Data folder should already include, among other things, an original Satellites.txt and SatelliteMagnitudes.txt. Rename these files by adding a single character like a % or ^, and Starry Night won’t recognize them. Copy the two new files into this folder, and the next time Preview Suite boots up, it will load with the Starlink satellites instead of the usual ones. These satellites can be highlighted on the Preflight side and should become visible on the Renderbox side of Preview Suite at the same time.

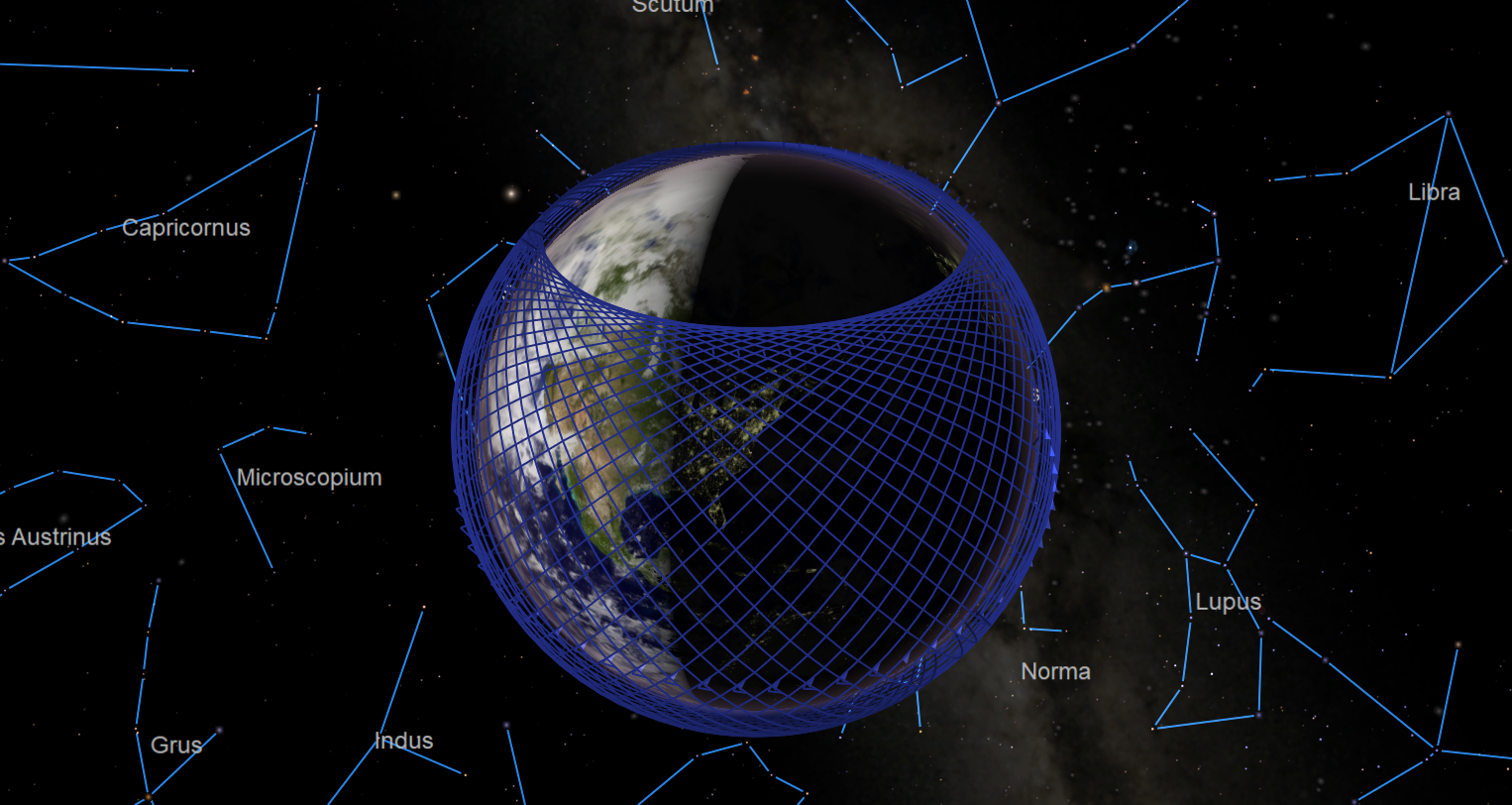

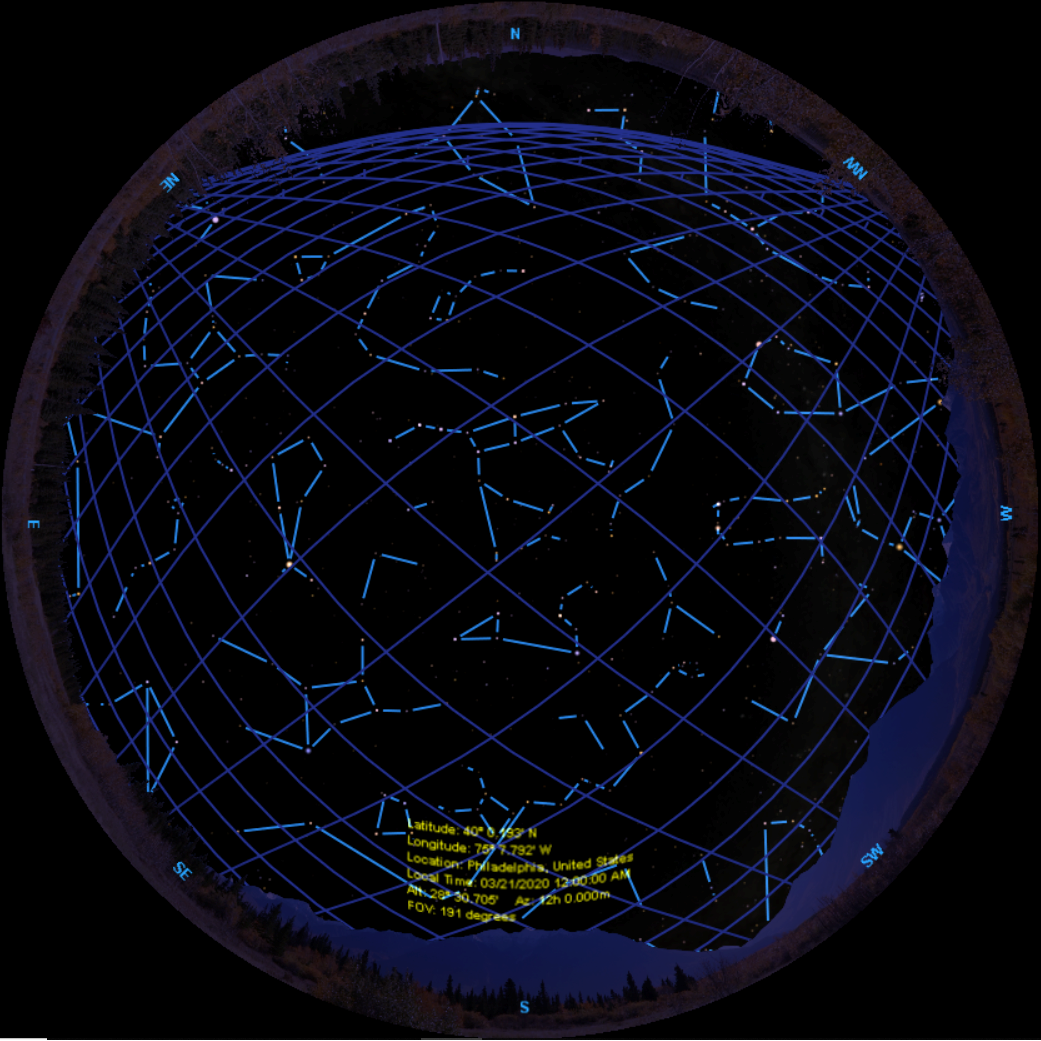

In these images, don’t think of the blue lines as real. They are just Starlinks with the orbit lines turned on. Think of each blue line segment as the path of each Starlink over the course of about 30 seconds, each blue diamond representing four of them.